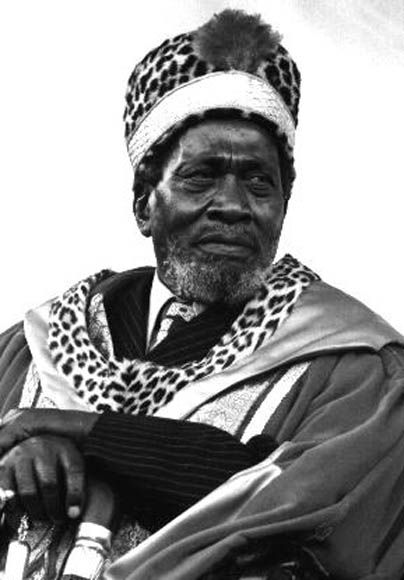

The Rule of

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta

1963 – 1978

1963–1978

The Rule of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

Elections were held in May 1963, pitting Kenyatta’s KANU against KADU, the Akamba People’s Party, and various independent candidates; the former were victorious with 83 seats out of 124. On 1 June 1963, Kenyatta was sworn in as prime minister of the autonomous Kenyan government. He was the country’s first Prime Minister to come from its indigenous population. Kenya remained a monarchy, with Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state. In November 1963, Kenyatta’s government introduced a law making it a criminal offence to disrespect the Prime Minister, with exile as a punishment. Kenyatta’s personality became a central aspect of the creation of the new state. In December, Nairobi’s Delamere Avenue was renamed Kenyatta Avenue, and a bronze statue of him was erected beside the country’s National Assembly. Photographs of Kenyatta were widely displayed in shop windows, and a likeness of his face was also printed on the new currency. In 1964, Oxford University Press published a collection of Kenyatta’s speeches under the title of Harambee!

Kenya’s first cabinet included not only Kikuyu but also members of the Luo, Kamba, Kisii, and Maragoli tribal groups. In June 1963, Kenyatta met with the Tanganyikan President Julius Nyerere and Ugandan President Milton Obote in Nairobi. The trio discussed the possibility of merging their three nations (plus Zanzibar) into a single East African Federation, agreeing that this would be accomplished by the end of the year. Privately, Kenyatta was more reluctant regarding the arrangement and as 1964 came around the federation had not come to pass. Many radical voices in Kenya urged him to pursue the project; in May 1964, Kenyatta rejected a back-benchers resolution calling for speedier federation. He publicly stated that talk of a federation had always been a ruse to hasten the pace of Kenyan independence from Britain, but Nyerere denied that this was true.

In December 1964, Kenya was officially proclaimed a republic. Kenyatta became its executive President, a role combining the head of state and head of government. Over the course of 1965 and 1966, various constitutional amendments were made that enhanced the President’s power. For instance, a May 1966 amendment gave the president the ability to order the detention of individuals without trial if the security of the state was regarded as threatened. Kenyatta sought to attain the support of Kenya’s second largest tribal group, the Luo, thus appointing the Luo activist Odinga as his Vice President. However, the Kikuyu—who made up around 20 percent of the Kenyan population—still held most of the important government and administrative positions in the country. This contributed to a perception among many in the country that independence had simply seen the dominance of a European elite replaced by the dominance of a Kikuyu elite.

Kenyatta’s calls to forgive and forget the past was a keystone of his government. He preserved various elements of the old colonial order in his administration, particularly on issues of law and order. The police and military structures were left largely intact. White Kenyans were left in senior positions within the judiciary, civil service, and parliament, with the white Kenyans Bruce Mackenzie and Humphrey Slade being among Kenyatta’s top officials. Kenyatta’s government nevertheless rejected the idea that the European and Asian minorities could be permitted dual citizenship, and expected that these groups should offer their total loyalty to the independent Kenyan state. His administration pressured whites-only social clubs to adopt multi-racial entry policies, and in 1964 schools formerly reserved for European pupils were opened to Africans and Asians.

Kenyatta’s government recognised the need to cultivate a sense of a united Kenyan national culture. To this end, it made efforts to assert the dignity of indigenous African cultures which had been belittled as “primitive” by the colonial authorities and missionaries. An East African Literature Bureau was created to publish the work of indigenous writers. The Kenya Cultural Centre supported indigenous art and music, with hundreds of traditional music and dance groups being formed; Kenyatta personally insisted that such performances were held at all national celebrations. Support was given to the preservation of historic and cultural monuments, while street names referencing colonial figures were renamed and symbols of colonialism—like the statue of Hugh Cholmondeley, 3rd Baron Delamere in the city centre of Nairobi—were removed. The government encouraged the use of Swahili as a national language, although English remained the main medium for parliamentary debates and the language of instruction in schools and universities. The historian Robert M. Maxon nevertheless suggested that “no national culture emerged during the Kenyatta era”, with most artistic and cultural expressions reflecting particular ethnic groups rather than a broader sense of Kenyanness and Western culture remaining heavily influential over the country’s elites.

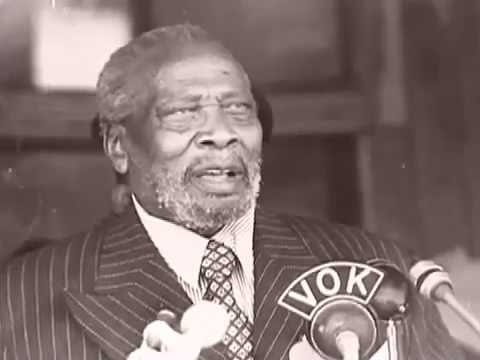

Feature on Jomo Kenyatta in 1977

Read the Latest Kenyan News.

Shaping the Political Front

News