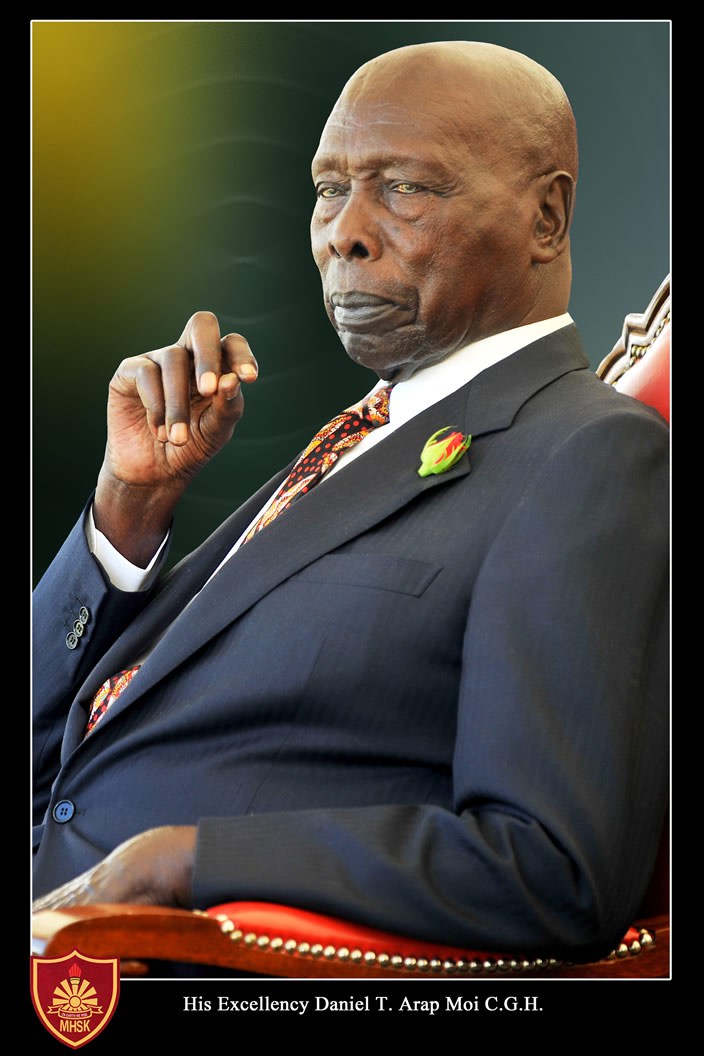

The Rule of

Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi

1978 – 2002

1978 – 2002

The Rule of Mzee Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi

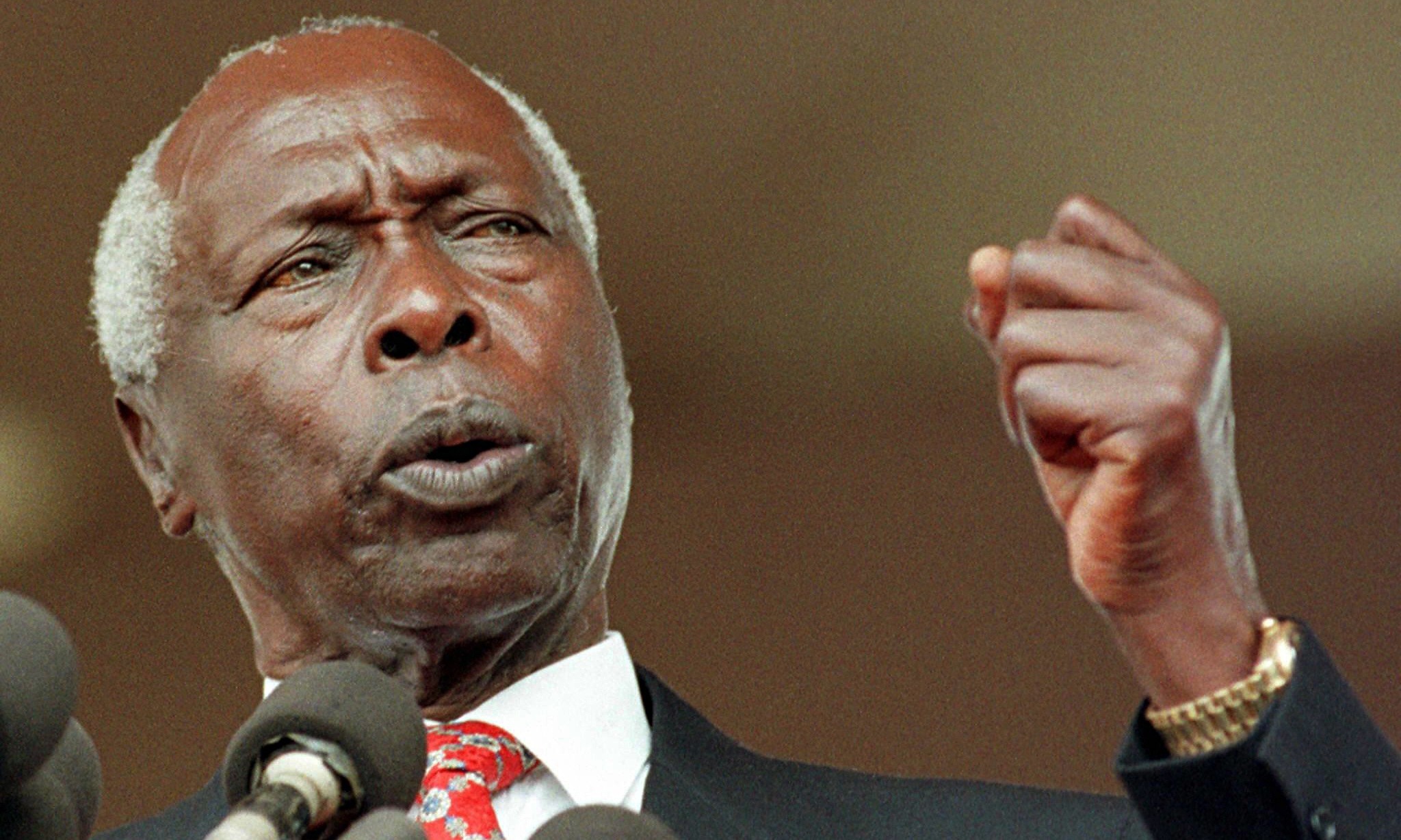

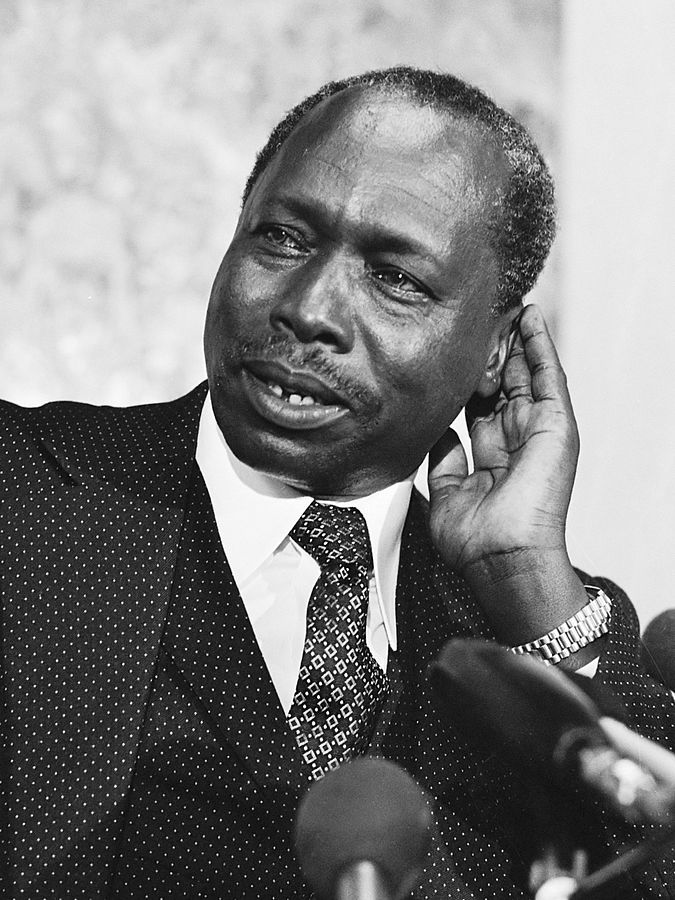

When Jomo Kenyatta died on 22 August 1978, Moi became acting president. Per the Constitution, a special presidential election for the balance of Kenyatta’s term was held on 8 November, 90 days later. Moi was the sole candidate.

In the beginning, Moi was popular, with widespread support all over the country. He toured the country and came into contact with the people everywhere, which was in great contrast to Kenyatta’s imperial style of governing behind closed doors. However, political realities dictated that he would continue to be beholden to the Kenyatta system which he had inherited intact, including the nearly dictatorial powers vested in the presidency. Despite his popularity, Moi was still too weak to consolidate his power. From the beginning, anticommunism was an important theme of Moi’s government; speaking on the new President’s behalf, Vice-President Mwai Kibaki bluntly stated, “There is no room for communists in Kenya.”

1982 Attempted Coup

On 1 August 1982, lower-level Air Force personnel, led by Senior Private Grade-I Hezekiah Ochuka and backed by university students, attempted a coup d’état to oust Moi. The putsch was quickly suppressed by military and police forces commanded by Chief of General Staff Mahamoud Mohamed.To this day it appears that the attempt by two independent groups to seize power contributed to the failure of both, with one group making its attempt slightly earlier than the other.

Moi took the opportunity to dismiss political opponents and consolidate his power. He reduced the influence of Kenyatta’s men in the cabinet through a long running judicial enquiry that resulted in the identification of key Kenyatta men as traitors. Moi pardoned them but not before establishing their traitor status in the public view. The main conspirators in the coup, including Ochuka were sentenced to death, marking the last judicial executions in Kenya. He appointed supporters to key roles and changed the constitution to formally make KANU the only legally permitted party in the country. However, as mentioned above, Kenya had been a de facto one-party state since 1969. Kenya’s academics and other intelligentsia did not accept this and the universities and colleges became the origin of movements that sought to introduce democratic reforms. However, Kenyan secret police infiltrated these groups and many members moved into exile. Marxism could no longer be taught at Kenyan universities. Underground movements, e.g. Mwakenya and Pambana, were born.

Moi’s regime now faced the end of the Cold War, and an economy stagnating under rising oil prices and falling prices for agricultural commodities. At the same time the West no longer dealt with Kenya as it had in the past, when it was viewed as a strategic regional outpost against communist influences from Ethiopia and Tanzania. At that time Kenya had received much foreign aid, and the country was accepted as well governed with Moi as a legitimate leader and firmly in charge. Western allies deliberately overlooked the increasing degree of political repression, including the use of torture at the infamous Nyayo House torture chambers. Some of the evidence of these torture cells was eventually to be exposed in 2003 after Mwai Kibaki became President.

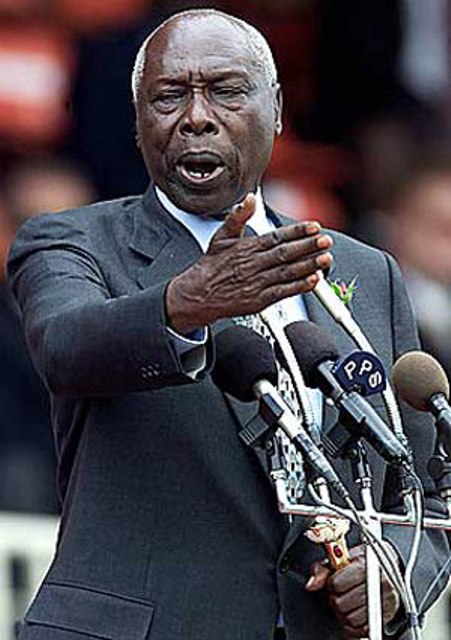

However, a new thinking emerged among Western policymakers after the end of the Cold War, and as Moi increasingly was viewed as a despot. Foreign aid was withheld pending compliance with economic and political reforms. One of the key conditions imposed on his regime, especially by the United States through fiery ambassador Smith Hempstone, was the restoration of a multi-party system. Despite his own lack of enthusiasm for the multiparty system, Moi managed to win over his party who were pro-single party, single-handedly convincing the delegates at a convened KANU conference at Kasarani in December 1991.

Moi won elections in 1992 and 1997, which were marred by political violence on both sides. Moi skilfully exploited Kenya’s mix of ethnic tensions in these contests, especially smaller tribes’ ever-present fear of domination by the larger tribes. In the absence of an effective and organised opposition, Moi had no difficulty in winning. Although it is also suspected that electoral fraud may have occurred, the key to his victory in both elections was a divided opposition. He always won the election with a minority vote of about 30% against the opposition who had a combined 70%, which was nonetheless of no consequence because it was subdivided among the opposition who had failed to unite.

Feature on Jomo Kenyatta in 1977

Read the Latest Kenyan News.

Shaping the Political Front

News